From Giles, 12/7/19

Among the wonderful people we’ve met here in Kinshasa, Jean Felix Mwema has made a deep impression on us. He has committed his life to being an activist for change in the DRC, where much change is badly needed. For brevity, I’ll call him JF, and he invited us to a cleanup project last Saturday, for a whole section of the city. We were among nearly fifty people who walked the streets with big black plastic bags picking up waste. It was quite a sight. And it caught the attention of people in the neighborhoods we passed through. The fact that four of us were white no doubt added to the surprise on the faces of people watching, either in the little shops along the way or other pedestrians or those in vehicles dodging us.

Apparently some onlookers began asking why people (especially white people) were doing this. Were we getting paid? So JF and his community organizers took time to explain (in Lingala or French) that this was voluntary and that the intent was not just to clean up but to encourage people to take pride in their city.

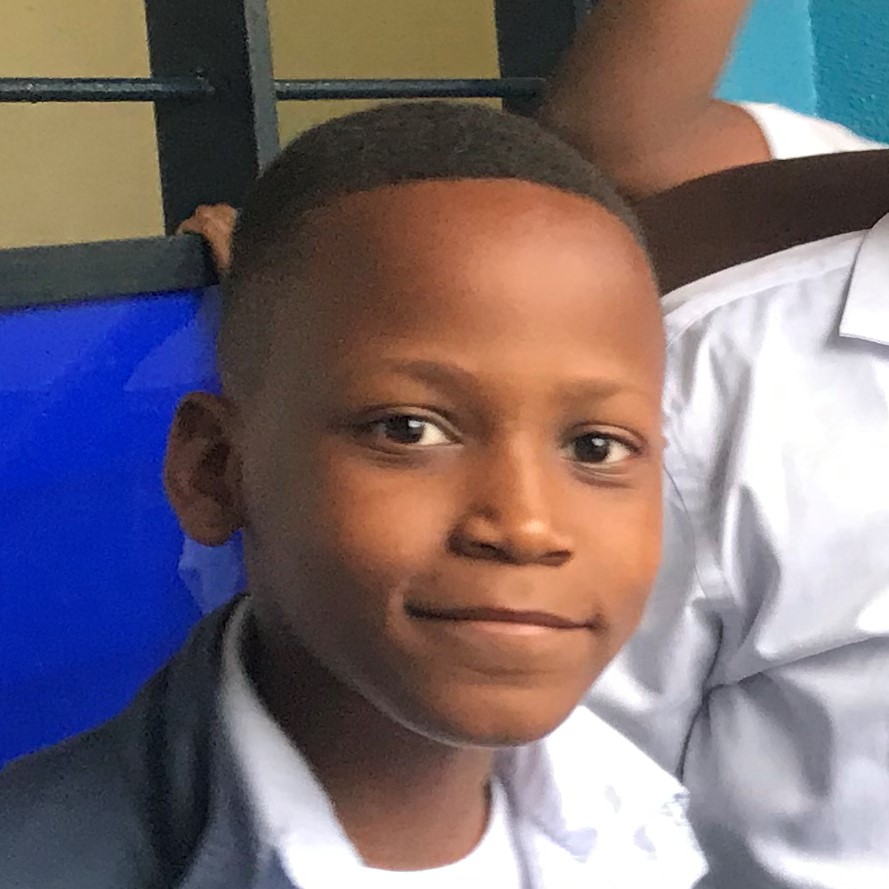

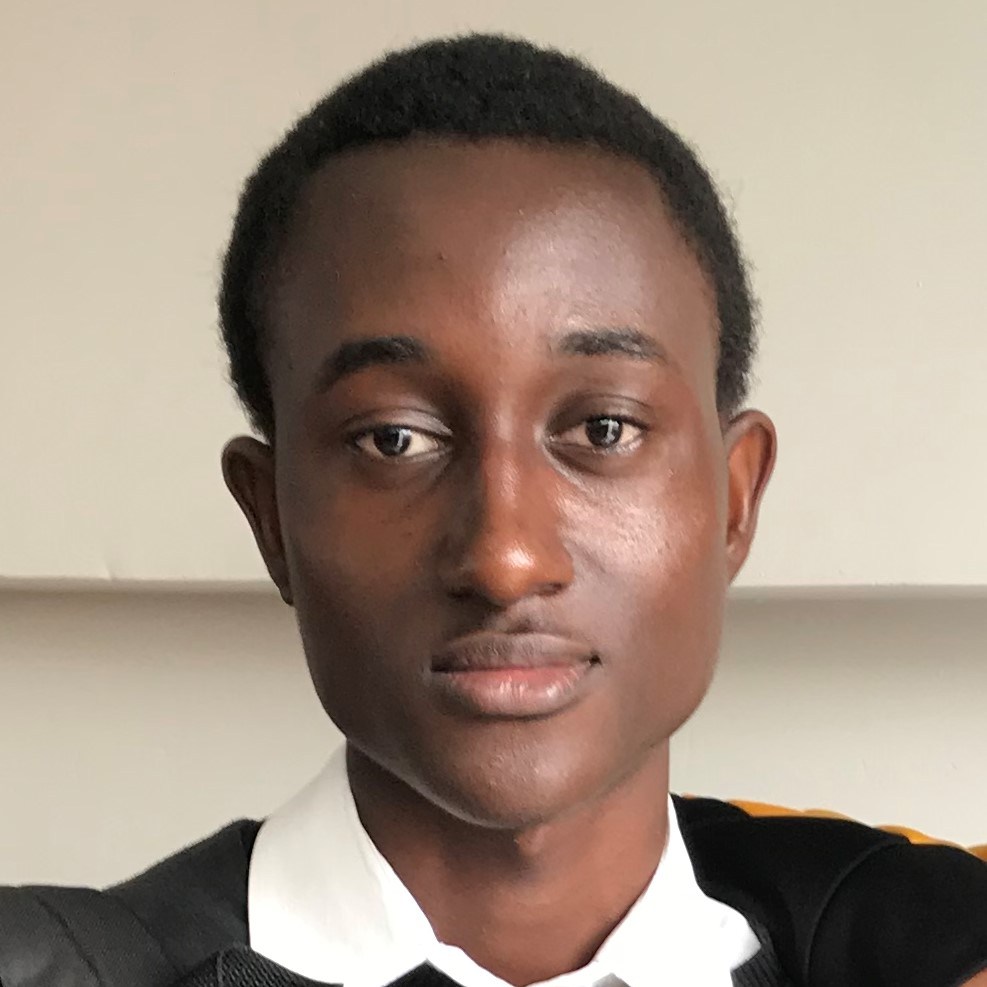

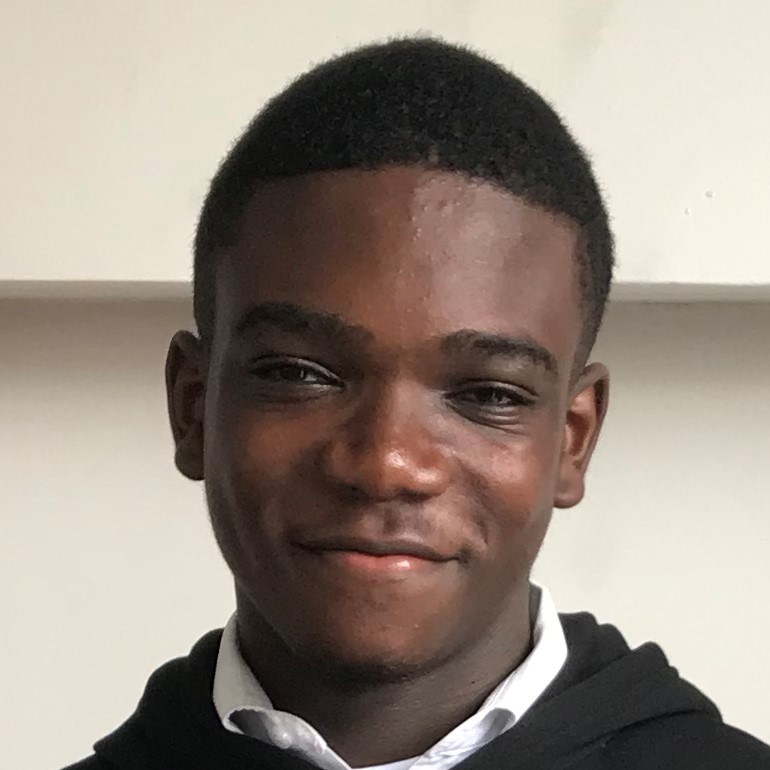

For us, the highlight of the morning’s work was the curiosity of the children who began to join in the process. At first just following us inquisitively in small groups staring at us, they were soon rushing around us picking up trash and stuffing it in our large bags with enthusiastic satisfaction. By the time we were through at noon, kids from five or six to sixteen clustered around us working vigorously. Along the way many of them had picked up our discarded rubber gloves and masks and—amid envious looks of their friends—and were wearing them with pride.

Though we barely made a dent, we helped make a statement, and we connected with hundreds of people in a worthwhile effort. Seeing the looks on people’s faces and sharing the delight in helping make a place look cleaner gave all of us a sense of purpose and unity.